TT® Trade Surveillance Cross-Product Spoofing Surveillance Models Whitepaper

TT Trade Surveillance's Composite Instrument Technique for Detection and Classification of Cross-Product Spoofing

What is Traditional Spoofing?

Over the course of the last decade, federal regulators and self-regulatory organizations (SROs) around the globe have made a concerted effort to eliminate manipulative trading activity known as spoofing from the capital markets.

For example, spoofing has been illegal under the Dodd-Frank Act since 2010 and is defined as: “bidding or offering with the intent to cancel the bid or offer before execution” (United States, 2010, p. 1739). [Source: Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act]

Initially, there was confusion about exactly what type of trading activity would fall under this broad definition, and there was a great deal of debate about whether or not spoofing should be viewed as anything more than savvy trading.

Regulators ended these debates through a series of high-profile enforcement actions, which reached their zenith in September of 2020 when JP Morgan was required to pay a $920 million fine for spoofing activity in the precious metals and treasury markets, the biggest-ever settlement imposed by the CFTC to date. [Source: JPMorgan to pay $920 million for manipulating precious metals, treasury market]

In addition to the monetary fines, the CFTC has worked closely with the Department of Justice to bring criminal charges against individual traders who have engaged in spoofing activity, resulting in convictions for fraud and prison terms ranging from 1–3 years. [Sources: CORRECTED-U.S. high-speed trader sentenced to 3 yrs in jail for spoofing, fraud; Two former JPMorgan traders sentenced to prison for fraud; Ex-Deutsche Bank trader gets year in prison in spoofing case]

Through these aggressive regulatory actions, financial industry participants have generally agreed upon a defined pattern of trading typically referred to as “traditional spoofing,” which involves spoofers manipulating the displayed order volume in the limit order book (LOB) to persuade market participants to trade in the spoofer’s desired direction. And, while spoofing can come in many different forms, it is frequently described in published regulatory actions as a pattern where a trader submits large orders or layered orders on one side of the market that the trader, then cancels after receiving fills on the smaller order(s) that the trader entered on the other side of the market. [Sources: TT Help Library > TT Score > > Spoofing > Spoofing Patterns; NYMEX Notice of Disciplinary Action]

CME Rule 575 and the ICE Disruptive Trading Practices rules also provide very insightful information about what factors are considered by regulators in assessing potential spoofing activity. These factors include, but are not limited to, the following {Sources: CME Group Market Regulation Advisory Notice; ICE Futures U.S. Disruptive Trading Practices FAQs; Cadwalader Clients & Friends Memo]:

- Whether the market participant’s intent was to induce others to trade when they otherwise would not;

- Whether the market participant’s intent was to affect a price rather than to change their position;

- Whether the market participant’s intent was to create misleading market conditions;

- The ability of the market participant to manage the risk associated with the order(s) if fully executed;

- The change in the best offer price, best bid price, last sale price or other price that results from the entry of the order; and

- The queue position or priority of the order in the order book.

In the UK, spoofing is not a specified offense. However, spoofing behavior may contravene civil and/or regulatory provisions in the EU Market Abuse Regulation (MAR), which has direct effect in the UK, and/or amount to a criminal offense under the Financial Services Act 2012 or the Fraud Act of 2006. In the U.S., the trader’s intent is pivotal. To prosecute spoofing, U.S. authorities must prove that there was intent to cancel the order at the time it was placed. In the UK, however, authorities generally focus on the impact of the spoof order on the market. While there is limited UK case law to date, in general terms the trader’s intent may be irrelevant in a UK civil case or less central in a UK criminal case than in a case under U.S. law. [Source: “Spoofing” the market: a comparison of US and UK law and enforcement]

Through a combination of the aforementioned rules and disciplinary actions, regulatory agencies have made it clear that financial firms of all varieties are now absolutely required to have a trade surveillance system in place to identify traditional spoofing, and they are also required to implement robust education programs to educate their traders about traditional spoofing. Firms that fail to meet these requirements will be held accountable by regulators for failing to supervise any traders that engage in traditional spoofing, and the traders themselves can certainly face criminal charges for their actions as well.

It is important to note, however, that even though regulators have had significant success in “stamping out” traditional spoofing from the capital markets, that does not mean that they are going to rest on their laurels.

In recent regulatory releases and during speeches at industry events, the regulators have made it clear that their focus is now shifting from traditional spoofing to a different and more complex form of trading manipulation commonly referred to as cross-product spoofing.

Compared to traditional spoofing where the trading behavior occurs in a single LOB, in a cross-product spoofing scheme, a trader may place larger orders in one product on an exchange or other trading venue with the intent of artificially impacting a related or “correlated” product trading on a different exchange or other trading venue. The secondary products have prices that are related to or correlated with the economics of the primary product, or they may be derivatives linked to the primary product. [Source: Cross-Market Manipulation Allegations: Economic Implications]

There are three main reasons why a spoofer might adopt what might seem like a much more complex strategy:

- First, because of the vast number of potentially correlated financial products, detecting such a spoofing case is more challenging. For example, how does a regulator or compliance officer have the ability to understand the full scope of potentially correlated products available for trading around the globe.

- Second, if the products are traded on different exchanges, then the regulators at those SROs will be required to cooperate and share information with each other in order to identify the pattern of trading activity occurring in the separate LOBs. This creates additional work for the regulators, and not all regulators are cooperative.

- And third, cross-product spoofing might expose the spoofer to less market risk and hence be cheaper than single-market manipulation due to relatedness among markets, but differences in depth and liquidity. The logic is similar to hedging. To minimize transaction costs, traders typically seek the cheapest possible hedge among assets or instruments that are considered to be most liquid—yet closely related to the asset to be hedged. [Source: Cross-market spoofing]

For example, In September 2018, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) settled charges against Victory Asset Inc. and Michael D. Franko for spoofing and cross-market manipulation in U.S. and UK markets. The CFTC imposed civil monetary penalties on Victory and Franko of $1.8 million and $500,000, respectively. [Source: CFTC Orders Futures Trader and Trading Firm to Pay $2.3 Million in Penalties for Cross-Market and Single-Market Spoofing and Manipulative Scheme]

Franko’s scheme involved cross-product spoofing, in which Franko placed his spoof orders and genuine orders in different, but correlated, markets (i.e., copper futures on COMEX and LME). For example, Franko placed one or more spoof orders in copper futures on COMEX to benefit a genuine order that he placed in copper futures on LME, taking advantage of the correlation in price between these markets. Franko also placed one or more spoof orders in copper futures on LME as part of a scheme to benefit a genuine order he placed in copper futures on COMEX.

In another example, in April 2022, the CFTC filed a civil enforcement action against David Skudder, Global Ag LLC, and Nesvick Trading Group LLC for spoofing, where some of their misconduct involved cross-market spoofing—i.e., spoofing in one market to benefit a position in another market, where the price of the two markets is correlated. [Source: CFTC Charges Tennessee Trader and Two Entities with Engaging in Cross-Market and Single-Market Spoofing and Manipulative Schemes]

The complaint alleges that from approximately September 2014 through March 2019, Skudder carried out his schemes by placing hundreds of large orders for soybean futures that he intended to cancel before execution (spoof orders) while placing orders on the opposite side in the soybean futures market, or cross-market in the options on soybeans futures market (genuine orders), that would benefit from market participants’ reactions to his spoof orders. By placing the spoof orders, Skudder allegedly deceived other traders about supply and demand, misleading market participants about the likely direction of the commodity’s price, which made Skudder’s genuine orders appear more attractive to market participants and allowed Skudder to execute his genuine orders in larger quantities and at better prices than he otherwise would have, absent the spoof orders.

And in the most recent high-profile cross-product spoofing matter, in November 2023, FINRA announced that it had fined BofA Securities, Inc. $24 million for engaging in more than 700 instances of spoofing through two former traders in U.S. Treasury secondary markets and related supervisory failures spanning more than six years. [Source: FINRA Fines BofA Securities $24 Million for Treasuries Spoofing and Related Supervisory Failures]

The complaint alleged that from October 2014 through February 2021, BofA Securities, through a former supervisor and a former junior trader, engaged in 717 instances of spoofing in a U.S. Treasury security to induce opposite-side executions in the same Treasury security or a correlated Treasury futures contract.

The 717 instances of spoofing were comprised of (a) 525 instances of spoofing in a U.S. Treasury security to induce opposite-side executions in the same security, and (b) 192 instances of cross-product spoofing in a U.S. Treasury security to induce opposite-side executions in a correlated U.S. Treasury futures contract.

The 192 instances of cross-product spoofing followed the same general pattern:

- The BofAS supervisor would enter a series of four non-bona fide orders to buy the 30-year bond to induce executions of two bona fide iceberg orders to sell the correlated Ultra T-Bond at the best offer price ($193.65625).

- While the BofAS supervisor displayed the full quantity ($50 million par value or 50 lots) of each non-bona fide order, he entered each bona fide order as an iceberg, with just one contract or lot ($193,656 notional value) displayed. Each $50 million non-bona fide order established the best bid of $103.75 for the 30-year bond and created an imbalanced stack.

- Within one second of entering each non-bona fide order, BofAS received favorable executions on a bona fide order and then canceled the non-bona fide order (typically also in less than one second).

TT Trade Surveillance Introduces Composite Instrument Technique for Cross-Product Spoofing Detection

In response to the recent shift in regulatory focus, Trading Technologies has patented a new method for identifying cross-product spoofing called the Composite Instrument (CI) technique.

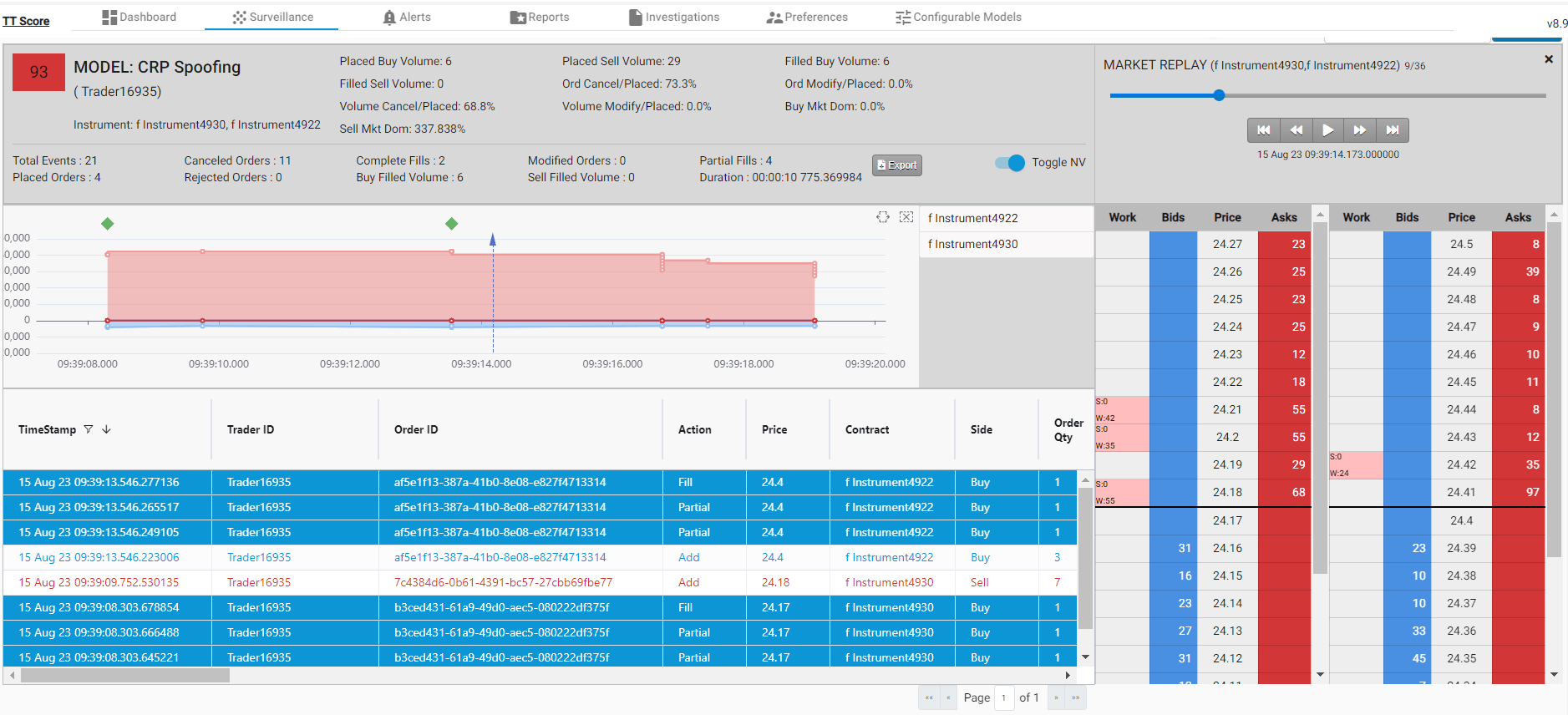

TT’s intuitive Cross Product (CRP) Spoofing model interface.

At a high level, when TT Trade Surveillance initially processes the order audit trail data of each trader in an organization, the new CI technique analyzes the trading activity to identify moments of potential overlapping activity across products and markets. When such overlap is detected, it triggers the creation of a CI that is specific to that set of traders on that particular day.

Next, TT Trade Surveillance engages in a second round of processing with the CI-specific Cross Product (CRP) Spoofing models, using the newly created underlying metrics of that particular CI. Machine Learning (ML) and advanced feature calculations are applied during this processing, and clusters are created and scored daily like the traditional TT Trade Surveillance Spoofing models (see TT Help Library).

In order to leverage this new CI technique, the user must first select products that they believe might be correlated in the cross market tab (see TT Help Library), and the TT Trade Surveillance CI system will look for all instrument variants of those products automatically in each processing run going forward.

Users can create any number of correlation groups, and there is no limit to the number of products that can be added. And of course they can be edited or deleted at any time. This is a low-touch, “set it and forget it” system with immediate impact.

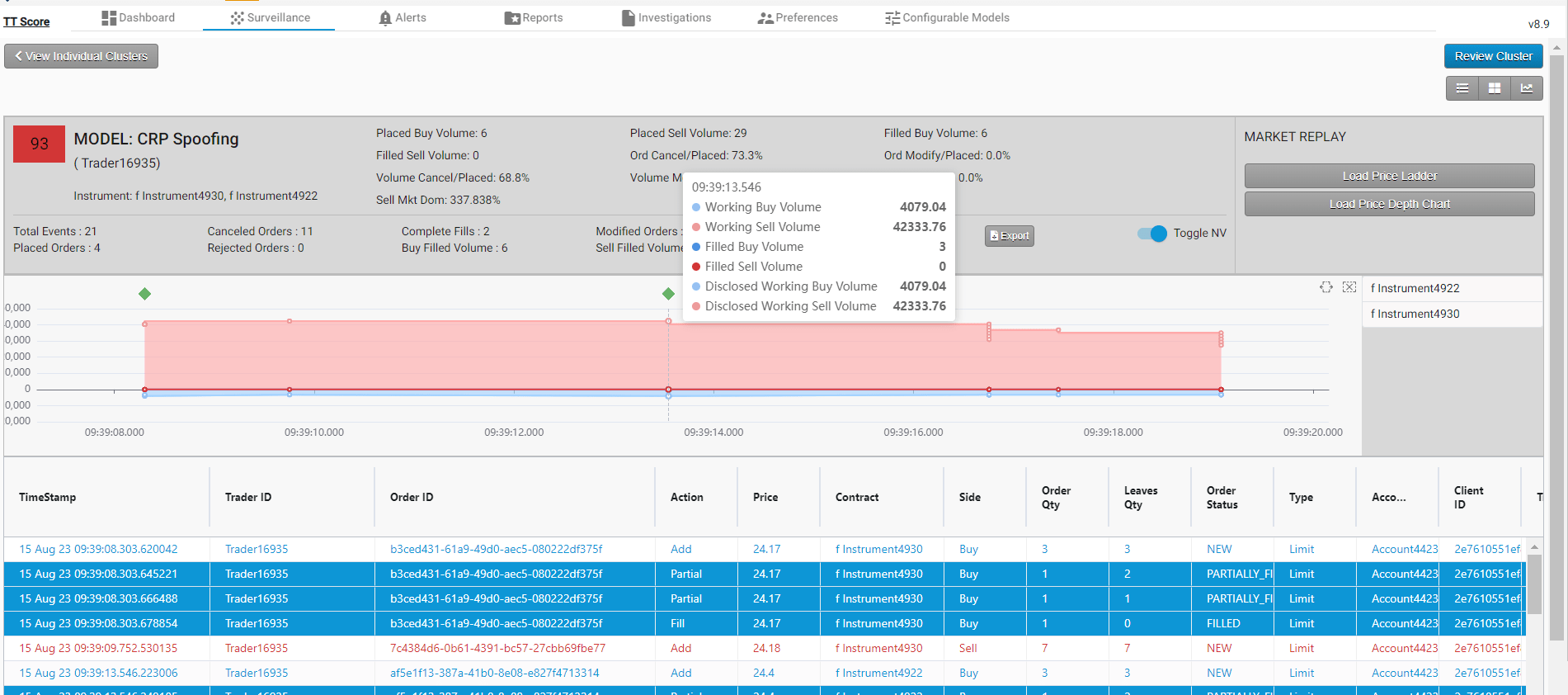

It is also important to note that the TT Trade Surveillance CRP Spoofing models measure LOB imbalance across multiple products by looking at the notional value of the order quantities in the multiple LOBs (see TT Help Library).

Viewing notional value in TT Trade Surveillance.

And finally, TT Trade Surveillance’s CRP Spoofing models also incorporate market data features that check for order quantities in the CI LOB to ensure that the order quantities involved can influence other market participants and reduce false positives.

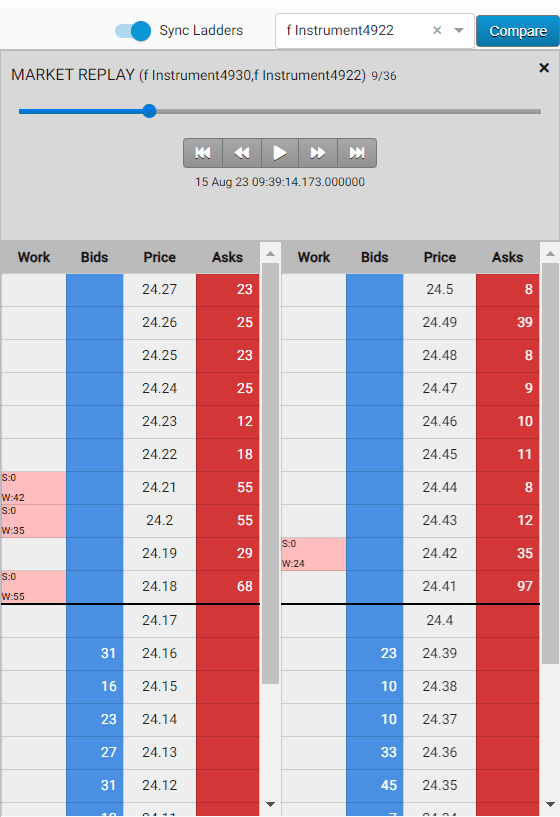

Visualizing Cross-Product Spoofing: Dual Market Ladder Replay

Dual Market Ladder Replay in TT Trade Surveillance.

Visualizations help compliance officers and regulators better understand the market; they allow them, among other things, to identify and understand anomalies such as spoofing.

In TT Trade Surveillance, we have always provided the user with the ability to visualize trading activity with the Market Ladder Replay tool.

However, because cross-product spoofing involves activity across more than one LOB, we have now created the ability for users to visualize trading activity across multiple LOBs with our new Dual Market Ladder replay tool (see TT Help Library).

For more information about TT Trade Surveillance’s capabilities, including detection of cross-product spoofing, please contact your TT Sales Manager or complete our online inquiry form.